Topics

Nudging, using behavioral economics

2024-01-31

Already been nudged today? Have you been nudged to do something? Literally, a nudge is nothing more than a gentle impulse. This article itself is hopefully a nudge, but there is a whole concept behind the term nudging. In short it’s about how we humans make decisions and the ways to nudge good decisions.

But slowly, two examples provide clarity. Some drivers have a hard time driving at an appropriate speed. Maybe then painted speed bumps help. Or smokers are reminded of consequences with a smoking zone in the shape of a coffin. What do these examples have in common? Everyone can speed over painted speed bumps and smoke as much as he wants. Those are just little nudges that are supposed to influence our behavior.

In 2008, the U.S. economist Richard Thaler and the legal scholar Cass Sunstein presented nudging in an entertaining and informative way in the book “Nudge: The Gentle Way to Improve Decisions”. According to this, a nudge is a gentle guidance of individual decisions and should have the following characteristics:

… must leave a choice.

… must be transparent.

… must not be misleading.

… must be to the individual’s advantage from a rational point of view.

… must be to everyone’s advantage from a rational point of view.

All other action triggers are manipulation and are called sludges, evil nudges or dark patterns in the specialist literature. The advertising industry knows these very well. The basis for any kind of action triggers is behavioral economics, with biases and heuristics. Thaler and Sunstein crack open some of these mechanisms of behavioral economics for us in their book. Hundreds of such behavioral mechanisms can be found in an immense amount of offline and online publications.

Even four small examples can illustrate such biases and heuristics well:

Anchor effect: If you visit a good restaurant with your customers, the wine list with a top price of 280 € in your hand, then the bottle for 60 € seems to be a quite reasonable choice.

Overestimating yourself: not heeding a warning because you are a professional. Or as surveys show again and again; 90% of drivers think they are above average drivers, although above average can be max. 50%.

Salience bias: Highlighted options are preferred. Well, already confirmed a (highlighted) cookie banner today?

Confirmation bias: Options are chosen that confirm one’s self and correspond to one’s (biased) experiences.

Homo economicus and homo sapiens

Behavioral economics attempts to explain real human behavior on the basis of biases and heuristics in decision-making situations and to use them for a decision architecture. Thaler and Sunstein distinguish between homo economicus and homo sapiens. Homo oeconomicus is absolutely rational. He decides on the basis of all available information; if this is not sufficient, he works with probabilities. You know such sentences of Mr. Spock: ” … with a probability of 76 % we will all die when rescuing the away team.”

On the other hand, Homo sapiens is subject to judgment biases and heuristics. We humans do not act rationally. Maybe possible in some areas of our actions. But in all? No. We are by far not as rational as we believe ourselves to be. We think we are master in the house, but we are not. This thought itself is already a distortion of judgment.

These two types represent two different systems of cognitive processing, the automatic system and reflective system.

Automatic system

Uncontrolled

Effortless

Associate

(Linking)

Fast

Unconsciously

Learned

Reflective system

Controlled

Strained

Deductive (Derivative)

Slowly

Conscious

Controlled

The automatic system works quickly and instinctively … we duck when a ball comes flying at us unexpectedly. We use the reflective system to decide, for example, on a structuring method in our new CCMS. We humans make the vast majority of all decisions with our automatic system. This is where nudging comes in. With a simple nudge, we nudge the decision maker in a direction that is advantageous for him, without depriving him of his freedom to make decisions.

Nudging strategies

To avoid unfavorable decisions due to judgment biases and assumptions, there are typical nudging strategies and combinations. With a nudge, individuals are supposed to choose the alternative they would rationally choose with all the information, just as a homo economicus would do.

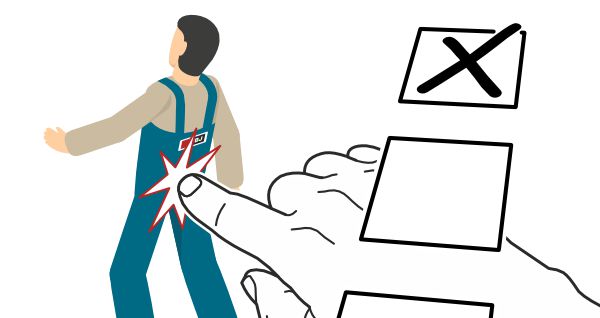

Defaults: The classic, checked checkbox for double-sided printing.

Simplification: Make forms user-friendly and simple.

Social norms: Inform gas consumers that their neighbors use less gas than they do to encourage conservation.

Simplicity: Actually, making the best option easily accessible.

Disclosure: Customers are informed of current consumption and costs by their electricity supplier to support economical consumption.

Warnings: We find warnings everywhere, from the famous notices on cigarette packs to the classic safety label. So we’re already nudging. Unfortunately, far too much, so this strategy has become a toothless tiger.

Self-commitment: People have a hard time sticking to goals they set for themselves. Disclosure of goals supports self-commitment.

Reminders: Taxpayers were successfully reminded that 80% of their neighbors had already filed their tax returns. Combining this with social norms was much more effective than a simple reminder.

Will to execute: People act more often when asked specifically about their intentions. E.g., in public restrooms with a small sticker “Hands washed?”. Combine this strategy with social norm, “Did your neighbor wash hands?” and you get a very effective nudge.

Consequence: Consequence is part of every warning or is also in the smoking area in the form of a coffin.

Dependence on situation and person

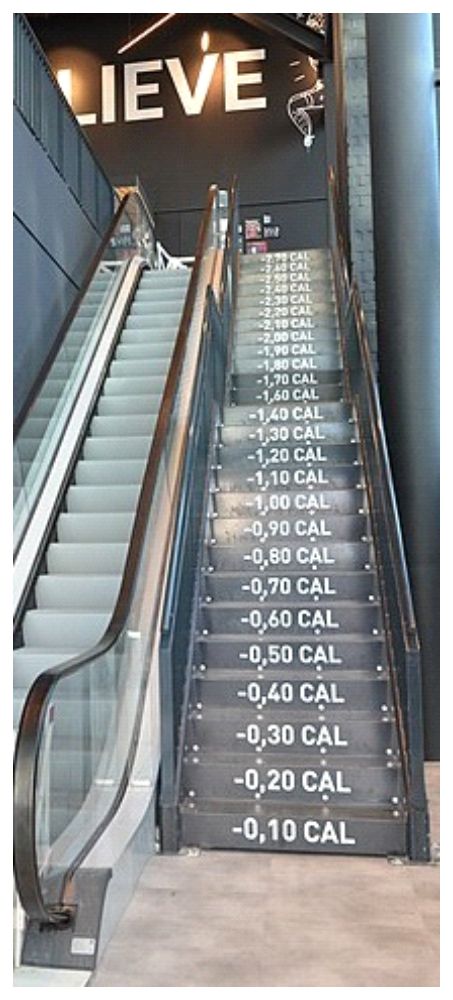

Basically, everyone wants to achieve positive results. With a nudge, information is given to achieve this. In the Figure here, this is done with consistency and disclosure in the form of lost calories with each step. This always works? No! Far from it, as we know from our “industry’s own” nudging strategy, the warning. Nudges depend on situation (place, time of day, time pressure, …) and person (age, character, preferences, …). In fact, the combination of escalator and stairs went to a gym and people were in “save calories” mode. A similar constellation at a train station would very likely not work as well. People have luggage, are in a hurry, or one variation is more crowded than the other.

And we can also nudge ourselves, with a knot in our handkerchief, like King Peter in Georg Büchner’s “Leonce and Lena”. King Peter tied a knot in his handkerchief to think of his people at least once a day, how generous. And here we are with our governments. Of course, governments want to influence the behavior of their citizens and have a toolbox to do so:

- Carrot

- Governments:

Subsidies - Technical Communication:

Gamification, Storytelling, Utility Films, Screencasts, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality

- Governments:

- Stick

- Governments:

Law and order - Technical Communication:

„…use only original spare parts, otherwise …”

- Governments:

Clarification

- Governments:

Flyers, websites, portals, databases, advertisements - Technical Communication:

Safety instructions and warnings

- Governments:

And new:

- Nudging

- Governments:

Defaults, simplify access - Technical Communication:

Defaults, Verfügbarkeit (Content Delivery Portal), Einfachheit

- Governments:

Thaler and Sunstein have now officially expanded this toolbox. Obama had it, Cameron had it, and so did many others, a Nuding Unit. State action is supposed to be effective, but lures, seductions and unnoticed influence on the psyche is something for advertising agencies, nothing for the rule of law, according to the often-heard opinion.

Libertarian Paternalism

Nevertheless, if one, with such a tool, goes to politics or is called by it, then you can not only call it nudging, but Thaler and Sunstein call it scientifically, libertarian paternalism. That sounds paradoxical or more correctly like an oxymoron, completely opposite. Something like “silent scream,” because libertarian stands for maximum freedom of choice and paternalism for a guardian style of politics. This doesn’t have to be a contradiction. A decision architect can grant freedom of choice and still nudge people in a certain direction so that they come to better decisions. Seduction for good, according to Thaler and Sunstein.

What could this mean for us?

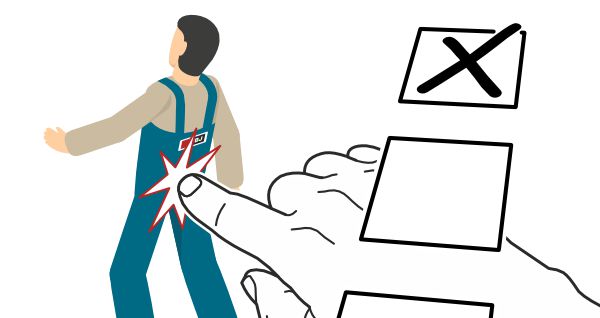

A survey of almost 1000 people from different companies on the use of protective devices on machines gave sobering results. 37% of guards had been permanently or temporarily tampered with, 80% of respondents did not feel unsafe, half saw the tampering as uncritical, 29% felt brave working on tampered machines, 33% felt guards were chicanery, and 5% did not even know they were working on tampered machines in the first place.

This is where biases and heuristics such as overestimation of self, peer pressure, convenience, desire to take risks, and consequence not being likely enough obviously come into play.

Manufacturers and we as technical writers respond with rational information; safety and warning labels, safety signs, and user information in general. But, as the survey shows, users act irrationally … all human.

So how about some instructive nudges. I have constructed two small examples here. The small problem is, we can typically only nudge in instructive text and illustrations, perhaps with labels and safety signs. The much bigger leverage in product design and UI is unfortunately missing for most of us.

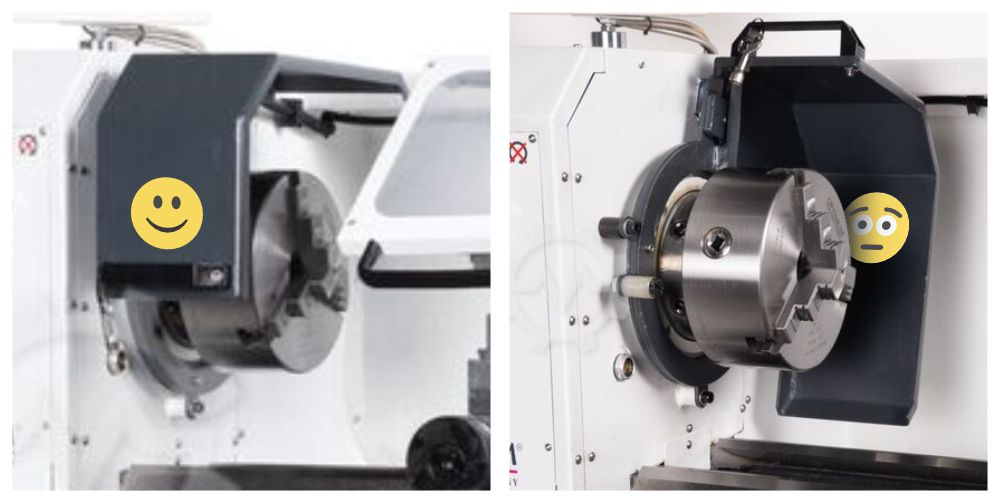

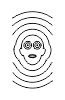

A very technical example, a chuck guard on a machine tool. If the chuck guard is closed, the user sees a laughing smiley, and if the guard is open, a worried smiley. A subtle and emotional warning that is also visible when the guard is open. By personifying the information, some social norm also plays into it and memory anyway. The properties for a good nudge fit if we assume that the user had a choice to leave the chuck guard open through manipulation. But let’s think about the dependencies of nudges. Will this work if users feel brave when working on tampered machines, or perceive guards as chicanery? Last but not least, the smiley in the chuck looks full of worry, as chips flying around will very soon have erased it.

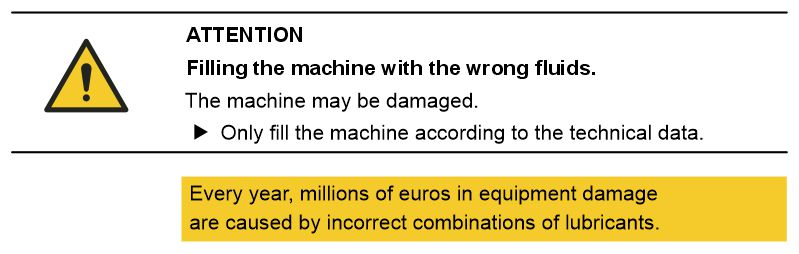

An instructive example, a warning of property damage. Mixing different lubricants can have very unpleasant consequences, if you are lucky nothing happens, with a little bad luck it flakes only a little and with a lot of bad luck the combination stops completely. I know what I am talking about, as a young maintenance mechanic I had the opportunity to learn a lot. The nudging strategies here is consistency and disclosure and the properties for nudges fit.

Decision architect from today

If we are aware of the mechanisms of behavioral economics with biases and heuristics in technical communication and understand how our users come to decisions, we develop information for Homo sapiens and not just for Homo oeconomicus and we can proudly call ourselves decision architects. Because, as we build our information buildings, the users make decisions.

In a nutshell: Nudging in instructions is very fuzzy, in product design much more effective. Legal effectiveness cannot be developed by nudging. Not very suitable for complex decisions, but for clear decision situations nudging can be well effective.

Whether you think about nudging or not, no one can escape behavioral economics.